Dr. Jörg Daur

Walking attentive and amazed throughout life

Opening speech by Dr. Jörg Daur, Deputy Director of the Wiesbaden Museum (2018, Kunsthaus Taunusstein)

A couple of months ago, when Tom Sommerlatte asked me whether I might be willing to talk about his pictures, I agreed without a moment’s hesitation.

I have known Tom Sommerlatte for many years. To be precise, I first came across him soon after I arrived in the Rhine-Main area at the end of the 1990s, and initially our acquaintance was rather one-sided and confined to the context of the Friends of the Museum Wiesbaden, where I did various odd jobs as a student. Among my duties was sending out exhibition information and the annual programme. At the time, it was a manageable task of some 300 envelopes. Today, with more than 1500 members, I would no longer be able to do it on my own.

Thus, our paths initially crossed indirectly, through the address on the envelope, so to speak. A little later, we also met at the museum itself, i.e. within the context and framework of art. What I didn’t know at the time – and admittedly didn’t know for a long time – was that Tom was an artist himself and had been working as an artist for most of his life. It was not until later, when we were both on the board of the Ritschl Society, that I got to know him not only as a profound connoisseur of art but also as a painter. For him, he said, the encounter with Otto Ritschl during the final years of the older artist’s life had been both an affirmation and an incentive to go his own way and to devote himself to working in colour.

At the age of twenty, Sommerlatte begun to study chemistry in Berlin. He had a facility with drawing but agreed to his parents’ wishes and went for something more ‘sensible’ first. He kept drawing ‘on the side’ – to indulge his passion, but perhaps also to compensate for the dryness of his scientific studies.

Right from the start, his compositions were informed by a sense of being carefully constructed; his images evolved from the motifs, and the motifs themselves were developed into grids or patterns. His drawings were clearly structured, ordered. The people they captured in sketch-like fashion did not really communicate, they were very cool, if that word was already current in the budding West Berlin jazz scene of the time.

Sommerlatte found his motifs in dance halls and clubs – chief among them the Eierschale, one of the buzziest jazz venues in Berlin in the late 1950s – and turned his impressions into existentialist collages and striking compositions.

Sharp lines established a sense of order in his pictures, traversed and defined the pictorial space and the picture plane, where soft forms were to dominate later. Built architecture with corners and edges formed tightly interlocked compositions that were marked by a dynamic tension across the picture plane.

But it was not until more than ten years later – by which time Tom Sommerlatte had made his home in the Taunus – that these early works gave rise to the organic forms that continue to shape his work today: corporeal, often erotic and – at least in terms of colour – lighter and somehow more poetic. Painting as an alternative to an oppressed, burdened world.

I have to say, though, that Tom Sommerlatte himself has always struck me as an optimist and as someone who is usually of good cheer. His manner is as infectious as it is soothing, and he has the wonderful ability to resolve problems and conflicts in the gentlest of ways. And this is exactly what we find in his paintings as well. Sommerlatte focuses on the basics, often chromatic harmonies or formal motifs, repeating them across the composition to show them in a different light.

His work is poised between figuration and abstraction. The early graphic series you can see in the exhibition already show figurative elements as well as half-abstract forms derived from them.

Spatially intertwined forms occupy the picture plane; rounded shapes form fantastic worlds, which Tom Sommerlatte describes as a ‘continent between Belgium and Luxembourg,’ i.e. as figments of the imagination, dream worlds or escapes.

And his paintings do indeed provide scope for our own thoughts, our own feelings to find inspiration in their sensitive palette. Sommerlatte’s colours tend to belong to a spectrum, which is to say they are tonal – cool or warm – and establish an overall mood. This is complemented by the intertwined forms that infuse the composition with a sense of order and, usually, harmony. The forms are rooted in figuration; not one of Sommerlatte’s paintings is purely abstract. Instead they recognisably draw on landscape, urban architecture or organic plant forms. When the human figure does make an appearance, it now is integrated in the overall composition, embedded in the ground rather than isolated as it was in the early existentialist pen and ink drawings.

Tom Sommerlatte consistently works in series. Already in the 1970s, he gathered his early drawings in print editions. This is showcased here by the juxtaposition of drawings and etchings, complemented by a selection of motifs interpreted in colour. What the display shows is how drawing, i.e. line and form, goes with painting, i.e. colour, while at the same time, the two can exist independently of each other.

Looking at three early editions, we can discern three fundamental themes: from landscape into the picture plane, the scrutiny of organic details and, finally, the human figure as part of the composition and, with it, of the cosmos of the picture.

Abstraction helps the artist to translate three-dimensional space into a flat surface; the individual elements of the composition are held in dynamic tension by the frame. The three paintings from Kassel, most strikingly here the lady with a parrot, already point in that direction. Sommerlatte uses columns and trees, flag poles or even just a few birds flying across the composition to establish an orderly rhythmic structure that sets the picture as a flat two-dimensional abstraction against three-dimensional space in which it is displayed.

The artist’s later works tend to feature more graphically conceived areas of flat colour. Set side by side, they derive their spatial definition from their tonal values alone.

Of particular interest in this context are the reliefs the artist has been producing in recent years. Unlike his paintings, they have great spatial depth and deliver the three-dimensionality the paintings only suggest. Although the individual forms are arranged in serried ranks, their conceptualisation remains strikingly graphic. Clear lines and edges define space and place the forms on different planes within it. The colour is more vivid and has less of an impact on the spatial order, which is already defined by the three-dimensionality of the relief.

And it is in the juxtaposition of the reliefs and the paintings that the infinitely nuanced colouring of the paintings really comes to the fore. Here the illusion of space relies on the handling of colour and form. And since the forms tend to be flat and intertwined, colour becomes hugely important. But Tom Sommerlatte seems less interested in an abstract, colour-generated sense of space than in suffusing his paintings with a range of colours that echo the light of the environment they depict.

The most recent paintings in this exhibition capture the mood of the morning, noon and evening at Fatih, the historic centre of metropolitan Istanbul. Near-identical in their arrangement of shapes on the canvas, the three paintings evoke the different times of day through colour alone. The pictures were painted in 2015 after an exhibition of the Wiesbaden artists’ group Künstlergruppe 50 in Fatih, a district of some 500,000 inhabitants which has been twinned with Wiesbaden since 2012. Here tradition and modernism coexist cheek by jowl. Tourist hotspots like the Sultan Ahmet Mosque, the hippodrome or the Hagia Sophia shape the borough as much as the large covered bazaar, the exotic bird market and the leaning wooden houses. The area is abuzz with life and age-old stories: a museum and the oriental heart of Istanbul.

It is not surprising that it was here that Tom Sommerlatte found inspiration for new paintings.

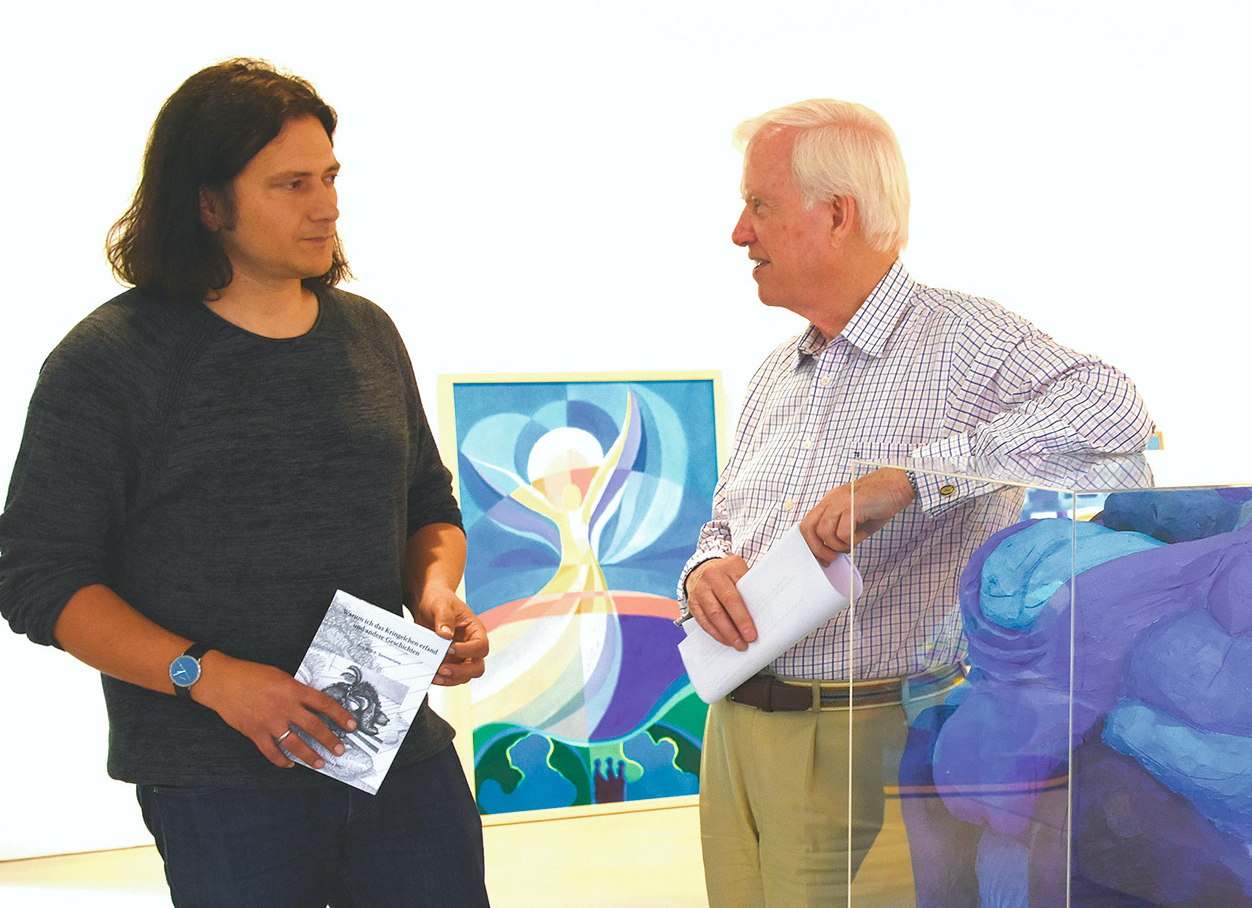

Multitalented, a painter and an artist, Tom Sommerlatte lives life with his eyes wide open, attentive and always ready to be amazed. When he was still at school, he wrote short stories for a newspaper column. In this exhibition we present not only the little book of select stories but also a few of the original illustrations.

I would like to conclude with a quotation from ‘Why I Invented the Squiglet,’ the text that lent its title to the publication:

‘Why did I invent the squiglet? Out of protest against the world of stone and corners in which I live, as a squeaky noise against the orderly sounds, as a giggle, as a grunt, as nonsense against the order.

Since inventing the squiglet, I find it much easier to bear the edges and cubes.’